OpenPath and the state of the supply chain

We all became more familiar with how supply chains work during the pandemic — because supply chains for many of our favorite products became constrained, supply tightened, and prices rose. Think about a pre-pandemic purchase of a Honda Civic. If it had an MSRP of $25,000, many of us would have been happy to transact somewhere between $22,000 to $25,000 before adding in any optional upgrades. At the height of the pandemic-fueled supply chain crisis, that same transaction would have been somewhere between $25,000 to $30,000 — and that’s only if you could get off the waiting list.

We accept those price fluctuations because we understand enough about that particular supply chain. There is enough transparency, price discovery, and competition to give us confidence to participate in the market and make the industry safe.

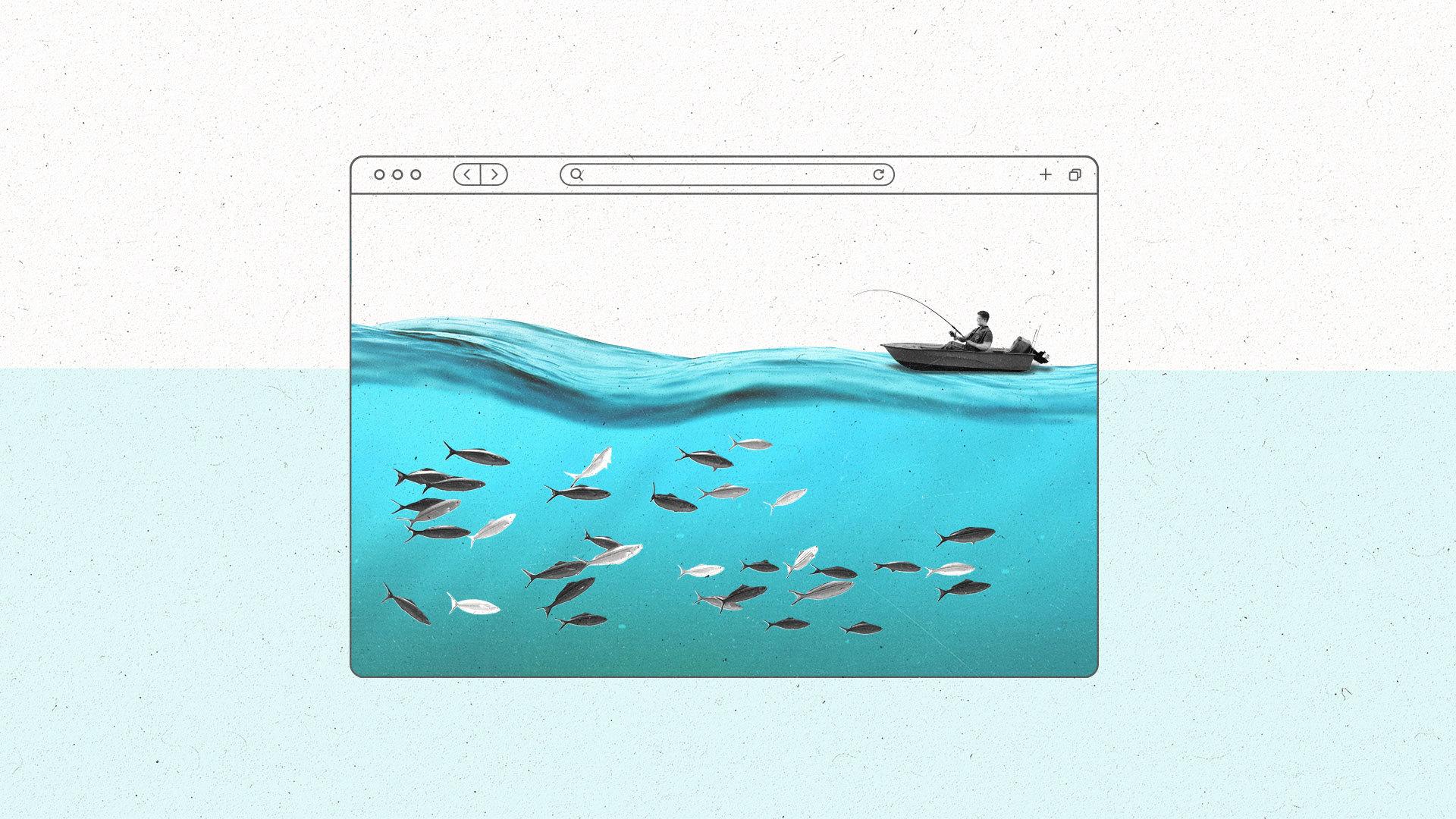

By comparison, the supply chain of digital advertising must be one of the most complicated and opaque of any scaled industry in the world.

A digital ad on the front page of a popular website could sell for $100 CPM (cost-per-mille — $100 to reach 1,000 viewers of the webpage) in one minute and for $2 CPM in the next. Certainly, there are some supply and demand variables that can impact those prices, particularly when you consider the difference in value of a particular website audience for different advertisers. And fungibility, utility, and perishability make digital advertising a much harder market to participate in to begin with.

But in many cases, the convoluted supply chain is the source of those wild price swings, particularly at the high end. Premiums may sometimes be the result of obfuscation and manipulation, as recently outlined by The U.S. Department of Justice’s (DOJ) antitrust lawsuit against Google. (BTW, in recent weeks, Google tried to have the case dismissed and its motion to dismiss was denied.)

There are many companies in the digital advertising supply chain that are actively trying to drive up the prices that advertisers pay — and not by a little — while trying to mask the fact that they are charging way more in cost to the supply chain than they add in value. The end result is that they’re often not trying to sell the car for $25,000 to $30,000 — but for the equivalent of $300,000.

A few years ago, I asked the founder of one of the major U.S.-based sell-side platforms (SSPs are ad tech companies that service publishers) one of the most important questions I’ve asked a partner in my role as CEO of The Trade Desk (TTD). I wanted to understand why his company was supporting Google’s DoubleClick for Publishers (DFP) — the ad server that Google acquired in 2007 and has renamed several times over the years — instead of competing with it. DFP is now the foundation of Google Ad Manager (GAM) and Open Bidding (OB) — the most misleadingly named product in the history of ad tech. Both products are at the heart of the DOJ lawsuit against Google.

I’ve said for years that DoubleClick was the most important acquisition in the history of ad tech because it has since become the decisioning tool for almost all web publishers and the primary source of measurement and reporting for internet advertising. Indeed, the DOJ asserts that DFP enjoys 90 percent market share on the supply side of digital advertising. It also was the starting point, as the DOJ alleges, of Google’s draconian measures to limit supply-side competition and obscure value for both advertisers and publishers.

For years, I had asked (practically begged) this esteemed U.S.-based SSP leader, as I have so many others, to provide an alternative to Google and DFP. I’ve even argued that not to do so would be to limit their own role to that of an ad exchange, offering much less incremental value, because ad exchanges represent standard and repeatable auctions. They would just be pipes. I could not understand why SSPs were not working harder to compete, to offer yield (revenue) optimization services for publishers — something those publishers are clamoring for. In my mind, the SSP business model depends on it.

His response to my question was ultimately very profound:

“I can’t compete. There is no way for any sell-side player to beat Google because of the demand that they bring from search. They have millions of advertisers providing demand for publishers in display and video. If a pub cuts out GAM, Google will not let their full demand go to another SSP. That’s the policy. It’s basically a monopoly. If a pub lets us do their yield management, they lose Google’s demand. I can’t compete with that.”

My company, TTD, represents the buy side — the world’s largest brands and their agencies. We believe our business is sustainable because we objectively help buyers decide what to buy. Using advanced data science and analytics, we help determine which ads are best for them to buy from the millions of ads available every second, to reach their target audience at the right time, at the best price. We don’t own media. We won’t own media. Our interests are aligned objectively with the buy side.

Just over a year ago, TTD launched a new product called OpenPath. It allows TTD to transparently share bids and asks with publishers via the open-source project Prebid. By doing so, we make room for SSPs and/or publishers to do real yield management. Hopefully over time it can help replace the black-box supply chain that Google controls with a better, more competitive, more transparent process.

This cleaner supply path is good for those SSPs and exchanges that add more value than they extract. Some SSPs are getting more as a result of OpenPath and some are getting less. This will continue as cleaner supply chains create consolidation and efficiency.

Because of the growth in demand that TTD brings to the buy side of the digital advertising market, in recent years I’ve been getting more interest from leaders of major publishers and media companies. They want access to our demand. And perhaps more important, they want to understand the dynamics of that demand. What are different advertisers willing to pay for any particular ad impression, for example. Because for publishers, even though they have the supply, they have very little line of sight into those demand dynamics.

Just before we launched OpenPath, I met with the CEO of one of the largest premium print publishers in the English-speaking world. Some of their brands existed before Truman or Churchill. The organization survived WWII, but digitization is an existential threat that has been their most challenging yet. Like so many others, he was looking for help.

His concern was that he didn’t feel that anyone was representing him in digital advertising. No one was really doing yield management for him, in his view. His ad inventory flowed at the whim of Google, and he had no idea what he could expect to be paid on any impression or why. He felt he didn’t have the power to manage certain auction dynamics, or understand all the settings, or track an impression end-to-end to know which SSPs added the most value. Google’s process was something he could not unravel. He was confident that SSPs were adding value in some cases, but he needed transparency and visibility to understand when and how.

He wasn’t even asking us to do yield management. He understands our role and that our value prop is focused on the buy side. He was simply asking for visibility into what we’d be willing to bid for those ad impressions. Without that insight, he was blind. Despite being sophisticated and reviewing all the data the market can provide him, he didn’t know who to work with.

I asked him what might happen if he rearranged the order in which his ads were auctioned in DFP, a fairly common tactic on the supply side of advertising. What would happen to his yield? His answer: “I have no idea.”

So, it’s complicated and messy. Got it. Now what?

These dynamics are no secret. And there are many companies in the industry working to improve the supply chain of advertising.

To be sure, both advertisers and publishers, over time, will gravitate to supply paths that offer transparency, and where value is clearest. For those who are making supply chains more opaque — or doing worse by exploiting its opaqueness — publishers and advertisers will find ways to work around them and will increasingly only use them when there is no other option. Some SSPs are already seeing incremental spend. Doing the right thing is becoming the best way to compete in ad tech, which hasn’t always been true.

To be clear, TTD isn’t offering to do yield management — the service of getting pubs the highest CPM. Our clients want high value and low (but fair) prices. OpenPath is quickly growing to do something very simple: open up visibility into the supply path. We have created a small but rapidly scaling simplified open path. It’s one way to solve the problem.

In my view, there are three ways to advance supply chain optimization and transparency from here.

One, the U.S. government prevails its lawsuit against Google and limits Google’s influence on the advertising supply chain. I maintain that this lawsuit is different than all those before it, but courts take a long time. The companies fueling the open internet would be fools to hold their breath while waiting for this one.

Two, Google decides to turn off a lucrative business in the name of creating a better supply chain for everyone (and potentially settling with the government). But that would require it to turn off a major moneymaker, which could risk substantially disappointing shareholders.

These first two options are unlikely, at least in the next few years. So, what are we left with? The only real solution is for leaders of the open internet to work together.

The open internet needs more innovations like OpenPath. Some streaming TV companies and other very large publishers will do their own yield management. After all, nearly every major connected TV (CTV) content owner in the U.S. has purchased an SSP in recent years or built the equivalent. Like them, some other large publishers will build their own ad servers and yield tools. But the vast majority will create new and clear relationships with SSPs to optimize revenue. SSPs will innovate to optimize yield from multiple places and avoid compromising the integrity of the auction. The presence of more metadata in the auction will make the supply chain healthier. There will be better price discovery and less fraud. That will only make the work of the demand side, on behalf of advertisers, more efficient.

Our ecosystem will keep getting better, so long as innovations to make the supply chain healthier keep coming.

The open internet has done some amazing things to raise all boats over the years — from OpenRTB, to ads.txt, or the seller standard technology of sellers.json, to OpenPath, to Unified ID 2.0, and, of course, to Prebid — not to mention all the work on viewability, measurement, and fraud prevention. The industry is taking this opportunity, as more advertisers and publishers become aware of a convoluted supply chain, to build something better.

And when the open internet works together while still competing fiercely, we will create a better supply chain, and almost everyone wins.

Subscribe to The Current

Subscribe to The Current