From Afrobeats to Nollywood: West African cultural exports could be the next big global content trend

First came Japanese media, with its epic manga, anime, video games, and armies of loyal otakus. Then it was Korean entertainment, with K-pop spearheading a global cultural wave, or hallyu, that included the first foreign-language “Best Picture” Oscar-winning movie (Parasite) and the first Korean act to headline the Coachella music festival (BLACKPINK).

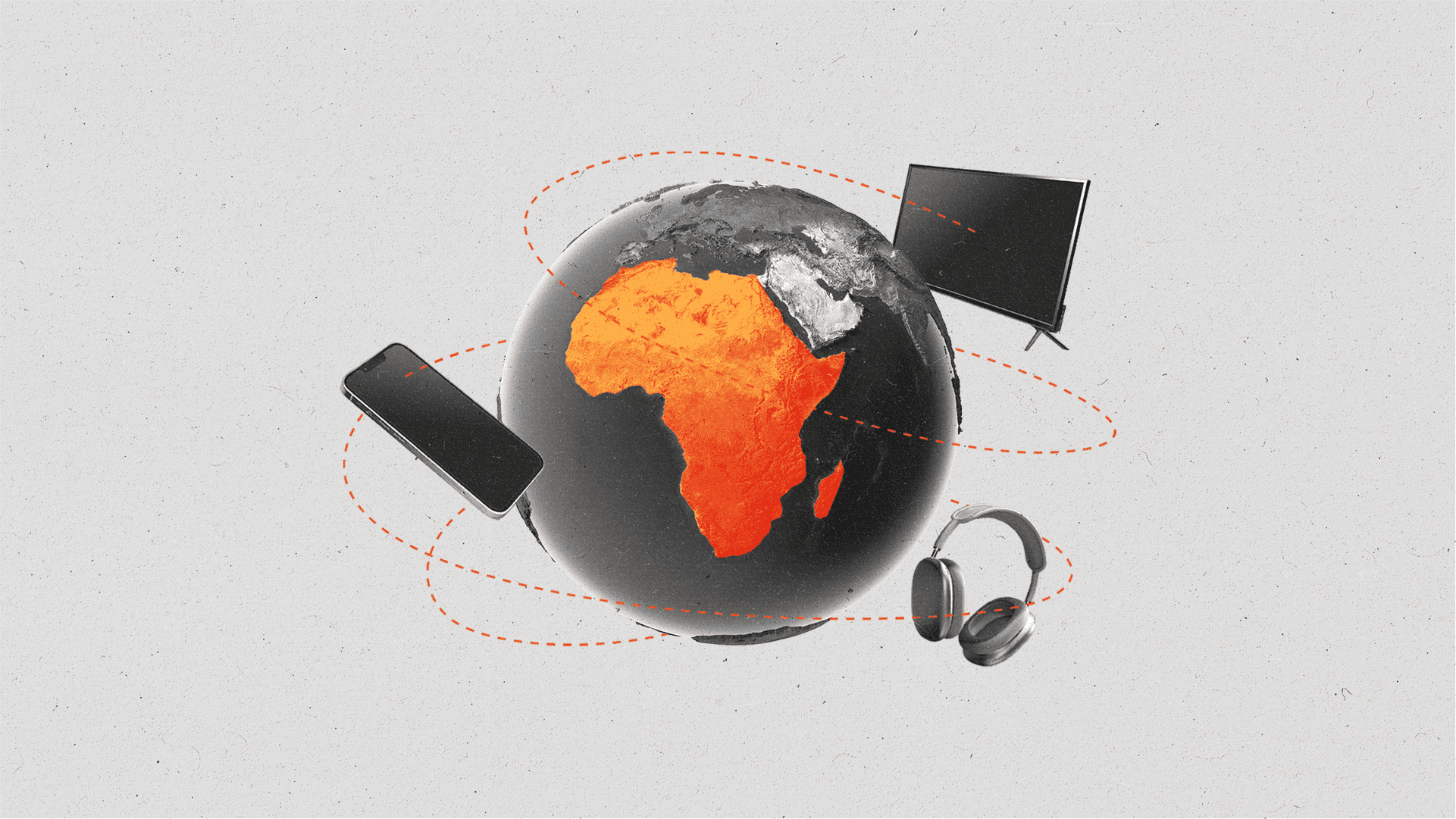

Now it could be West Africa’s turn to usher in the next big global trend in content.

Earlier this month, the Selena Gomez remix of Afrobeats star Rema’s song “Calm Down” became the first African-artist-led track to amass 1 billion streams on Spotify, joining the likes of Taylor Swift, Drake, and Coldplay at the uppermost echelon of the music streaming world. At the start of the month, Nigeria’s Burna Boy became the first international Afrobeats artist to land a No. 1 album in the U.K.

And American streaming giants have been steadily, if quietly, investing in African video content, especially out of Nollywood and South Africa, looking for the next Squid Game-like global hit. These investments could prove particularly fruitful as the Hollywood content tap sputters back to life following the end of the U.S. writers’ strike.

The surge in popularity of African (and particularly West African) content is the latest iteration of the globalization of media. The ubiquity of global streaming platforms means that content has no borders, with audiences in Brazil just as likely to stream Afrobeats music as those from India and the U.S., according to Spotify.

“It’s a paradigm shift. Global media consumers, particularly younger, more diverse, and tech-savvy audiences, are looking for representation and authenticity in the content they consume,” says Victoria Popoola, co-founder and CEO of TalentX Africa, a film-financing marketplace.

“There’s an interest in stories that either resonate with [consumers’] own experiences or provide insights into different cultures and perspectives. There’s also a significant diasporan market that’s interested in content that reflects their roots and heritage,” she adds.

This globalization bodes well for advertisers, as it creates audiences of often young consumers for marketers and brands to reach, unencumbered by physical borders — something that is happening in the sports streaming world as well.

Brands like Burberry and Savage X Fenty are already working with Afrobeats artists, mirroring the commercial success found by K-pop acts. Nollywood stars like Tobi Bakre, meanwhile, are being tipped for Hollywood success.

‘A winning formula’

Afrobeats is not one single genre, but an umbrella term often used to describe contemporary West African pop music.

At the start of the millennium, Afrobeats thrived in England’s Afro-Caribbean university rave scene. Now stars like Wizkid, Asake, and Burna Boy regularly sell out massive arenas like London’s O2 and New York’s Barclays Center.

“One would think that Nigeria is the biggest consumer of the Afrobeats genre, but in fact, both the U.S. and the U.K. are out-streaming them,” Jocelyne Muhutu-Remy, managing director for Spotify in sub-Saharan Africa, told Al Jazeera.

Afrobeats’ growth comes on the back of the global growth in music streaming, which now makes up 67 percent of music industry revenues. On Spotify, Afrobeats streams have grown by 550 percent since 2017.

“When you’ve got African swag and African traditions combined with up-to-date Western styles and singing in English, well — you’ve got a winning formula on your hands,” British-Ghanaian hip-hop artist Sway told The Guardian.

This points to Afrobeats as a great vehicle to reach new audiences, such as diasporic African communities in the West but also cohorts that are younger and more diverse. Afrobeats fans spend 121 percent more money on music categories per month than the average U.S. music listener, according to research from Luminate.

The media and advertising industries are noticing.

Burna Boy, together with Brazilian megastar Anitta, headlined the 2023 UEFA Champions League final in Istanbul in June this year, highlighting the appeal of non-Western entertainment for FIFA, the world’s governing body for soccer, which is on a global expansion trajectory of its own. In the U.S., Burna Boy was joined by Grammy winner Tems and Rema at a performance during the NBA All-Star Game this year.

Rema and Ayra Starr, another popular Afrobeats artist, were signed by Pepsi Nigeria as ambassadors last year, and Nike even released a pair of Jordan sneakers nicknamed “Afrobeats” by some.

“Brands are looking for ways to diversify themselves, diversify the audiences that they’re reaching, and Afrobeats is a great way to lean into that,” says Alison Bringé, CMO at Launchmetrics. She adds that Launchmetrics data shows that partnering with up-and-coming celebrities like Afrobeats star Davido can be a better marketing investment for brands than someone like Rihanna, and not just because of the lower sticker price. Their fans are more engaged, and the artists are keen to have a conversation with fans online, Bringé says.

Perhaps the biggest driver of Afrobeats’ recent popularity, however, is TikTok. Dance crazes such as those inspired by CKay’s “Love Nwantiti” and Ayra Starr’s “Rush” have helped propel the genre in front of global audiences, with singer Amaarae crediting music and social platforms for facilitating discoverability.

“It’s a paradigm shift. Global media consumers, particularly younger, more diverse, and tech-savvy audiences, are looking for representation and authenticity in the content they consume”

Victoria Popoola, co-founder and CEO of TalentX Africa

Indeed, data from Luminate shared with The Current by the firm’s VP and Head of Insights Nick Lanzafame shows that 69 percent of U.S. music listeners (ages 13 and up) engage with music from artists originating outside the U.S.

“Afrobeats, K-pop, and Latin are the most obvious examples of this, showcasing the changes in content appetites,” he says. “It will be interesting to see how that attention is used in creative ways by relevant brands across all industries in order to make organic and effective connections with audiences — especially as traditional advertising channels become less reliable.”

A rich cultural heritage and unique storytelling

Afrobeats isn’t the only growing cultural export coming out of Nigeria and West Africa. Output from Nigeria’s film industry, Nollywood, is quickly shedding its reputation of low-budget home-video productions.

Gangs of Lagos, which came out of Amazon Prime Video’s deal with Nigerian director Jáde Osiberu, defies the standard Nollywood movie, thanks to its compelling storyline and actors, as well as flashy action scenes.

“I wanted to tell this story and to show that this kind of film could come out of Nigeria,” Osiberu told The Hollywood Reporter. “Now just imagine what we could do when we even have an even bigger stage and more resources.”

Critics are also responding well to Nigerian films — Mami Wata took home the “World Cinema Dramatic Special Jury” award for cinematography at Sundance this year.

TalentX Africa’s Popoola says that at first, the relatively cheaper production costs meant that Western media firms were able to experiment with different film categories and test reception without taking on too big a risk.

“Nollywood used to be something that Nigerians consumed, and then foreigners would consume it in small bits and pieces as sort of like a guilty pleasure, and now it is morphing into an actual global industry,” adds Anita Eboigbe, a journalist covering the industry on her In Nollywood newsletter.

Nollywood’s growth comes at a time when streaming giants are not only looking for new, original content, but also seeing their own growth stall at home. Netflix, Amazon, South Africa’s Showmax, and other homegrown players are doubling down on sub-Saharan Africa as the next source of subscriber growth, with commissions in sub-Saharan Africa seeing the largest year-on-year increase of any global region last year.

The influx of money from streamers hasn’t just provided new avenues for budding filmmakers to distribute their creations. It has also enabled Nollywood productions to secure better equipment, institute quality control at an international standard, and craft stories that are more universal and understandable by people across cultures, says Eboigbe.

“You don’t need to have a lot of Nigerian context to understand the films, because there are stories that are universal, because the picture quality speaks to you,” she says. “All of these things did not exist before.”

Indeed, Eboigbe notes that when she started covering the industry, bigger productions were working with budgets of 50 million naira ($60,000). Things are different now: Nollywood’s first $1 million production, The Black Book, reached the fourth position on Netflix’s global chart during its release week and was among the top 10 films in 38 countries.

The global trending of Nigerian and West African cultural exports is a matter of when, not if, according to Popoola.

“We’re already on track for this — especially with films, music, and fashion,” she says. “West Africa has a rich cultural heritage and unique storytelling. Our music is already a big hit, and with the improvements in film production quality and storytelling, I believe our films are next.”

Subscribe to The Current

Subscribe to The Current newsletter